Luke Penner just returned from Las Vegas after competing in the World Advanced Aerobatic Championship with Team Canada. He was the top-scoring Canadian pilot at the competition and Team Canada ranked 4th overall, the best placement they’ve ever earned. The aircraft he flew, an Extra 330SC, will be on display at the Royal Aviation Museum until April 2024.

When he flew in yesterday to deliver his plane, we asked him about what it was like to compete at that level and what his future plans are.

RAM: Describe the experience of competing in the World Advanced Aerobatic Championship.

LUKE: Challenging, rewarding, and inspiring.

[Aerobatic pilots] do this sport because it’s hard, so it was challenging but in all the best ways. It makes you want to be better. You learn your weaknesses and get better. It’s a sport that weeds out ego very quickly.

Rewarding because the whole team aspect was really cool. [My teammates] were people I’ve flown against for years but the team dynamic changes things. There’s sharing of information and camaraderie. I have a bond with these guys that I’m going to have forever. I think we did a good job representing the country. There were about 15 countries there and each one had a tent and everyone always came to the Canadian tent. It was the place to be.

Knowing that a lot of the contestants were among the top 10 best pilots in the world, seeing what they’re doing, talking to them, learning their training strategies and seeing that they’re so welcoming was inspiring. People weren’t secretive. We just wanted to see each other do their best.

It’s also inspiring because everyone who’s there worked really hard to be there. The contest director opened up the competition at the opening ceremonies saying, “Everyone here is a winner,” because just to get here is very hard. The people in this sport, we’re the tip of the spear of the tiny number of people that do this sport.

For perspective, it’s estimated that in the United States there are 300,000 pilots. Of those, there are 4,000 members of the International Aerobatic Club. Of those 4,000, 250 regularly compete and only eight were on the (US) team.

RAM: Now that you’re targeting the Unlimited category, the highest level, can you explain what the different is between that and the Advanced category?

LUKE: In the lower categories like Sportsman or Intermediate you’d have a base figure, we call it a p-loop, because it’s in the shape of a ‘p.’ So imagine the airplane pulling up, straight vertical and then it goes up vertical and then you pull off that line and then you pull all the way around and do ¾ of a loop and then finish horizontally. That’s the base figure. If you move up in the categories you take the same base figure but you add stuff to it. You add rotational elements, different types of rolls, things like that. In Advanced, you would do something like: pull up to vertical, ¼ roll, a second ¼ roll, pull off the top and then maybe a full roll at the top of that loop, pull down and then all the way through. In Unlimited, you take the same figure and add way more stuff. For instance, you might pull vertical, do a ¼ roll, an opposite ½ roll, a whole roll over the top, then a snap roll at the top, go all the way down, then a ¼ roll, and finish with a 1 ¾ roll opposite. And that’s just one figure.

In addition to being more loaded with elements, there are numerous new figures that you do not do in Advanced. The main one being negative snap rolls.

RAM: What’s so different about these?

LUKE: They’re violent, they hurt, and they’re really hard.

RAM: Have you ever done one?

LUKE: I did 10 yesterday. That’s what the rest of my life is now.

I’ve dabbled in Unlimited for the last two years to get a taste for it. I’ve done a lot of the catalogue already but doing it within the confines of a sequence is a different thing. That will take lots of training in the spring. First competition is in June (in Iowa).

RAM: What do you do to train over the winter?

LUKE: The mental part is really important. Human beings were not designed to be upside down, so developing instincts so that when I’m up there I know what to do. Obviously, you rehearse it on the ground, but for instance, right now, the most complex rotational element I would do would be a maneuver called an inverted spin. So it’s the same thing [as a spin] but you do it upside down. When you are inverted, the movements of yaw and roll oppose each other. What that means is, if I’m upside down—this is what I do when I’m at home (Luke bends over so that his head is nearly between his legs). I walk like this because that’s what it looks like in the cockpit. I need to know which foot is it, or which direction the stick needs to move to achieve what I want to achieve. So, if I want to do a rolling turn, where the airplane rolls and turns in the opposite direction, if the airplane’s upside down and I want to do a ninety-degree turn, I’m turning one way but rolling the other way. I need to know which foot to use because it’s different when you’re upside down and it’s different whether you start upright or inverted. That kind of stuff is even more complicated in Unlimited. I need to know, instinctually, if I’m rotating inverted this way and then the rotational element that follows is reversed, I need to know what that means. It’s going to be a lot of programming myself so that when I get up there it’s instinctual. That’s what I did when I jumped up to Advanced. It was a lot of walking around the house with my head between my legs trying to think, “Okay, if I was here and I wanted to go that way, which foot is it gonna be?” Everything sounds easy when you’re sitting here right doing 1 g and zero knots but when you’re up there and you’re hanging by the straps and you have about one second to do the right thing, it comes down to instincts. So that’s just lots of rehearsing. That’s one blessing with Manitoba winters—I have a lot of time to think about this. Probably too much, but still, I’ll take that time.

And time at that gym. That’s big. Mainly upper body strength. This year I focussed on my shoulders a lot so that my neck was strengthened. Doing this stuff, you can really, really hurt yourself, the neck in particular. You’re doing rotational motion on g-loading and if you move your neck in a certain way—I found out the hard way last year—there’s a certain way to move your neck to reduce possibility of injury. Knowing how to move the head, no diagonal, just side-to-side and up and down. Knowing that I never hurt myself this year, even though I was flying my new plane which is much more violent. Last year I was down for two weeks. I couldn’t fly these (aerobatic) planes because I hurt myself so badly.

RAM: Is there anything else you’re going to do to prepare?

LUKE: (Laughs) I’m thinking of getting an inversion table so that I can hang upside down while I [run the sequences in my head]. No joke.

To learn more about Luke’s path to becoming a top-ranked aerobatic pilot, check out this post.

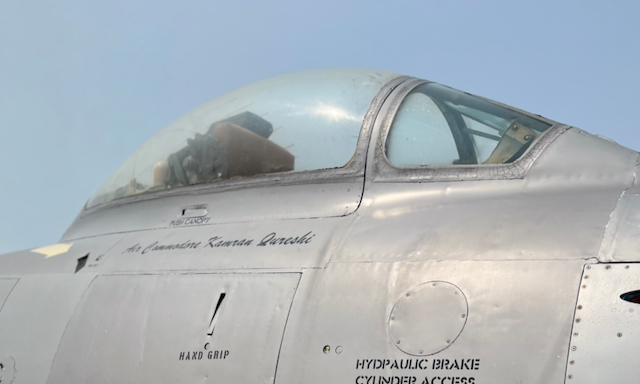

Be sure to stop by and see Luke’s Extra 330SC this winter!